A REVIEW OF

The End of the World Is a Cul de Sac

By Louise Kennedy

Penguin Random HouseHardcover; 289 pages

Female-centered short stories set in Irish countryside strike with darkness and wit

By Sarah Tramel

To be a woman is to be many things at once- unfaithful/too faithful, lost/looking, hopeful/hopeless. Through fifteen short stories, Louise Kennedy’s “The End of the World is a Cul de Sac” illustrates the multifaceted nature of womanhood, bound together by darkness. Sometimes dark tragedy, sometimes dark comedy and sometimes just darkness.

In the titular story, a wife is left with the desolate aftermath of her fleeing husband’s actions. Branded by her inaction amidst the spectacle, she warps reality into something palatable for herself. And an army of equally rich characters take shape in the pages to follow.

A woman, speaking with a thick regional accent, is mocked for her origin rather than listened to for her words. The parallel miseries of sisters Elaine and Siobhán seep with such casual disrespect from their men that grand gestures of betrayal don’t even sting. Two friends vacation in the wrong country at the wrong time in an effort to alleviate cancer and betrayal.

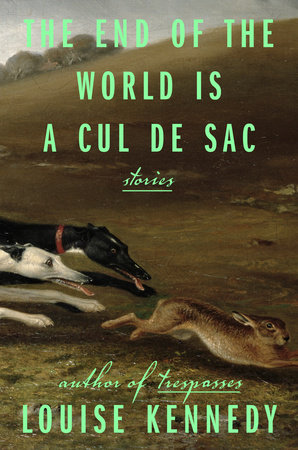

Peppered with delightful Irish vernacular like “craic” and “kitted out,” these stories, set in Kennedy’s native land, draw inspiration from its countryside. The women see themselves in the wildlife, hunted and flippantly discarded, like the hare in the story “Hunter-Gatherer,” which “screams like a woman when it’s hurt.”

Similar to other storytellers with the ability to keep an audience rapt (like Stephanie Danler), Louise Kennedy spent many years in the restaurant industry before becoming a writer. Something in that line of work seems to create the ability to see, really see, the world, and not shy away from portraying it honestly.

In “Brittle Things,” an isolated mother struggles with her son’s undiagnosed condition, which his father refuses to acknowledge. In “What the Birds Heard,” Doireann is faced with the decision of whether to both metaphorically and literally fill the space she has held for a man.

In “Sparing the Heather,” Mairead sees the grouse birds’ obliteration as happening slowly, though the very vocal men around her claim otherwise—a mirroring of her own “dying-off in tiny increments.”

If there is an underlying current of optimism to this collection of stories, it is that women have the strength to weather the unfathomable, however imperfectly. This resolve manifests itself in a variety of ways: quiet, loud, cautious, reckless, joyful, numb.

These stories see women becoming who other people need them to be: pseudo-widow, silent comforter, useful ornament, unseen stronghold. And the short story style allows for necessary open-endedness. Rather than provide answers, these tales leave us with important questions.

I feel that with every re-read of this collection, a new landscape of messages will reveal itself. And isn’t that what makes a really good story?

I leave you with this quote from “Brittle Things,” one of my favorites of Kennedy’s quippy one-liners: “It seemed to her that ‘you’re amazing’ meant ‘how do you tolerate your life?’”

Sarah Tramel is a medical resident and avid reader who lives in Belhaven with her husband, Robert, her daughter, Tindall, and her rescue dog, Leo. Her passions also include running, drinking wine on porches, dancing to live music, and adventures with her girlfriends.