A review of

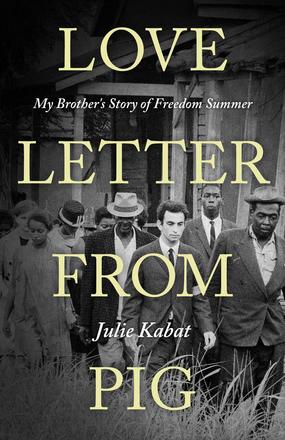

Love Letter from Pig

By Julie Kabat

University Press of Mississippi

Hardcover; 272 pages

Sister of Freedom Summer volunteer completes his memoir 50 years after his death

By Shira Muroff

Special to the Clarion-Ledger

“Love Letter from Pig” is a declaration of love from author Julie Kabat to her brother Lucien “Luke” Kabat. During the summer of 1964, Julie Kabat (called “Pig” by her brother) was at home in Rhode Island as Luke went off to Meridian, Mississippi to volunteer with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during Freedom Summer. While in Mississippi, Luke kept meticulous notes, initially scribbling thoughts on an airplane napkin. After passing away from cancer two years after his initial experience in Mississippi, and right before graduating medical school, he never got to write his planned book. So, fifty years later, his younger sister has taken up the mantle and brought readers into the movement and her brother’s mind in an engaging way.

While most readers have probably never heard the name Luke Kabat, more will know the name of the volunteer whose place he took in Meridian: Michael Schwerner. Julie Kabat relays the panic her parents had when hearing that Luke was taking over for someone who had disappeared and was presumed dead at the time. Both secular Jews, Luke felt a kinship with taking Mickey’s place to continue the work.

Kabat weaves together personal stories with the wider history into a manageable and accessible book. The richness of her brother’s Meridian tales sometimes makes the greater context somewhat clunky. However, as the book goes on, the narrative and the history become seamlessly connected. Kabat describes how her family was on the East Coast because anti-communist sentiment in California required her father to leave his medical job and relocate. Though secular, Jewish history and tradition had clearly made its impact on Luke. His volunteering was influenced by the Holocaust’s impact on his family only 20 years before. In a touching scene, Luke’s Jewish teachings and traditions come out almost by habit as he counsels and consoles his young students in Meridian as they navigate the deaths of Chaney (a student’s brother) and Schwerner (a favorite teacher).

Luke’s detailed notes are often scanned into the book itself, giving readers a sense of intimacy. Readers revisit the night that Pete Seeger announced to a crowd gathered in a Meridian church for a concert that the bodies of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner had been found. And as Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) staff, Luke is on the ground planning the Black community’s four-pronged walk to gather for James Chaney’s funeral. Kabat does not shy away from the fact that the Black adults and teens on the ground were the ones putting their lives on the line. Kabat highlights the experiences of Ben Chaney, James Chaney’s younger brother, and teen activists who were kicked out of their Meridian schools and hastily relocated to the Northeast to finish their education.

Kabat smartly goes beyond Freedom Summer, including Luke’s experiences in Atlantic City for the Democratic National Convention, and how even after returning to Stanford Medical School he used every opportunity to return to Meridian. Luke transferred the community organizing skills he learned in Meridian to East Palo Alto where he was based, work that led him to his wife Syrtiller. At the pre-wedding celebrations Kabat noticed that her brother wasn’t feeling well, and soon after he passed away from lung cancer.

Decades later, Julie Kabat wanted to teach her grandchildren about her brother. From searching friends and family members’ houses nationwide, to networking at the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer in Meridian, she was able to collect records, memories, and legacies.

A tale of a lesser known figure of Freedom Summer, Luke Kabat’s life can be summed up by this trio of experiences at his funeral: an appearance by Stokely Carmichael, Julie Kabat singing her brother’s favorite song, Seeger’s “Turn, Turn, Turn,” and a communal singing of “We shall overcome./ We shall overcome someday.”

Shira Muroff has been a Jacksonian since 2016, developing programs for southern Jewish communities and Mississippi history students. She is also a community editor for Rooted Magazine, a free, online magazine dedicated to telling stories of Place from the people who call Mississippi Home.